Kyrgyzstan has found itself among 75 countries for which the United States has temporarily suspended the issuance of immigration visas. This decision has sparked a strong reaction, but it is important to understand that it reflects not only America's migration policy but also its current attitude towards a country that previously undertook serious commitments to Washington.

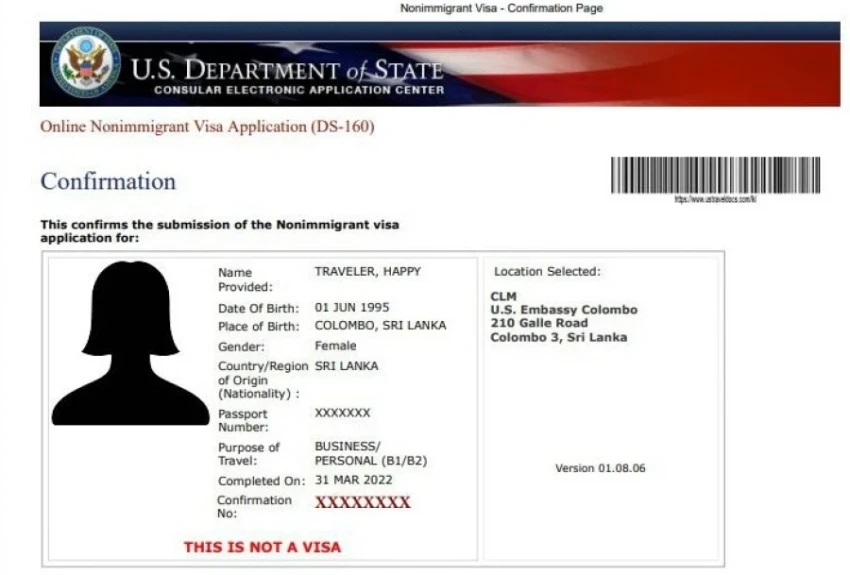

During a meeting with John Pommerhsime, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Central and South Asia, Kyrgyzstan's ambassador, Aibek Moldogaziev, tried to convey the importance of this aspect. He discussed the new visa restrictions, including the suspension of immigration visas, the need for a deposit of $5,000 to $15,000 for B-1/B-2 visas, and the possible reduction of business and tourist exchanges. These figures are not just statistics — they signify a reduction in human connections that have always been the foundation of Kyrgyz-American relations.

Pommerhsime replied that these measures are aimed at combating illegal migration. This sounds logical at first glance, but the compiled list of countries appears to disregard real relationships, the history of cooperation, and the level of reliability of partners. Kyrgyzstan has ended up on a general list of countries that Washington has included along with many states with varying levels of interaction.

Here arises a sense of injustice that cannot be expressed in diplomatic language, but is understood by anyone familiar with the history of relations between the two countries.

Since 2001, when the U.S. asked Kyrgyzstan to allow the establishment of the "Manas" airbase, the country has effectively found itself in a zone of strategic risks. Under pressure from neighbors and in a complex internal political situation, Kyrgyzstan agreed to open its territory for the anti-terrorist coalition, realizing the price it would have to pay for this.

The "Manas" base served not only as an airfield but also as a key point in Operation "Enduring Freedom," through which cargo, military personnel, and fuel passed. It became a logistical hub upon which the entire mission in Afghanistan depended. Over the years, Kyrgyzstan became an important partner but also faced political pressure and criticism.

Now, two decades later, it seems that Washington has forgotten this as easily as it changes outdated regulations. Kyrgyzstan, which hosted a strategically important base for a long time, is now viewed on par with many other countries with which the U.S. has far fewer points of interaction.

Trump bases his policy on limiting migration and reducing costs, reflecting his view of the world. However, it is important to remember political memory. Kyrgyzstan, which supported the U.S. in 2001, could have expected an individual approach and understanding of the context, rather than an automatic inclusion in a general list.

There is now a sharp contrast: on one hand, a business forum B5+1 is being prepared, meetings are taking place, and words about partnership are being spoken; on the other hand, barriers for people, businesses, and cultural exchanges are increasing. This creates ambiguity: the rhetoric of friendship exists, but practical steps are going in the opposite direction.

All this is happening against the backdrop of Kyrgyzstan once again finding itself caught between the political interests of major powers. This is not the first time, but that is why it is important to remember: for a small country, international decisions are never "technical." They always have economic, social, and symbolic consequences.

If the U.S. continues to perceive Kyrgyzstan as part of a long list of "risk countries," rather than as a former strategic partner, it means that Washington's foreign policy towards the region has become much less sophisticated than before. Bishkek, just like twenty years ago, is once again faced with a choice: will it be an object of foreign policy or will it try to assert its subjectivity.