For a long time, Altai in western Mongolia remained on the periphery of archaeological research in Eurasia. However, in their new book, William Fitzhugh and Richard Kortum present compelling evidence that this region occupies a key position in the development of nomadic societies, hunting cultures, and ritual landscapes. In this context, MiddleAsianNews informs.

The authors draw on years of field research around Lake Khoton and the surrounding valleys, where they have documented hundreds of petroglyphs and burial structures. They use glacial bedrock in both a literal and metaphorical sense, emphasizing a 20,000-year cultural continuity.

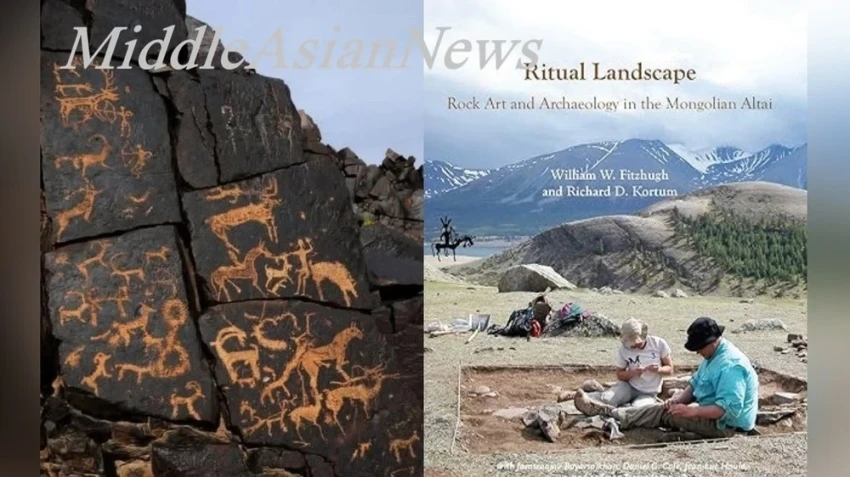

"Ritual Landscape: Rock Art and Archaeology of the Mongolian Altai" is a deeply researched and multilayered study that successfully combines the study of rock art with traditional archaeological methods, all set against the impressive geological landscape of the Mongolian Altai.

One of the key achievements of this work is its effort to unite two often isolated fields of science – rock painting and archaeology. The authors demonstrate that rock art, viewed in the context of burial architecture and the environment, becomes an important part of human history rather than just an aesthetic phenomenon. This approach allows for a reevaluation of petroglyphs as elements of ritual and social life associated with burials and ceremonial monuments.

One of the strengths of the book is its chronological scope. By tracing events from the Upper Paleolithic to the historical pastoral era, the authors demonstrate changes in subsistence strategies, mobility, and belief systems, many of which persist to this day.

The authors explore how the motifs of rock art evolve from depictions of large wild animals to the iconography of nomads. This sequence, based on stratigraphic data and stylistic analysis, is key to understanding changes in the lives of steppe peoples.

Another important aspect of this publication is its emphasis on landscape archaeology. The authors do not merely catalog objects but propose to view Altai as a ritualized space where hills, rivers, and mountain passes become participants in human history. The idea of the "ritual landscape" shows how visual and geographical features influenced the placement of images and monuments.

The book is rich in high-quality photographs, maps, and diagrams that enhance the narrative. The visual component plays an important role in this research, which is based on graphic sources and landscapes. Specialists in Central Asia, rock art, and nomadic societies will find this publication not only informative but also visually appealing.

It should be noted that "Ritual Landscape" not only answers questions but also raises new ones. It offers innovative methods for dating rock paintings, calls for the integration of iconographic and archaeological data, and encourages a reconsideration of the role of steppe societies as active cultural agents rather than mere migrants.

The impact on future research both in Altai and in other border areas will be significant.