Laboratory Study: The Myth That Boxing Caused Muhammad Ali's Parkinson's Disease

The question arises: could boxing have caused Muhammad Ali's Parkinson's disease? This topic generates much debate. Below we present one opinion on this matter:

Many believe that Ali's Parkinson's disease was a consequence of his boxing career. However, this assertion is questionable. We will attempt to refute it based on facts.

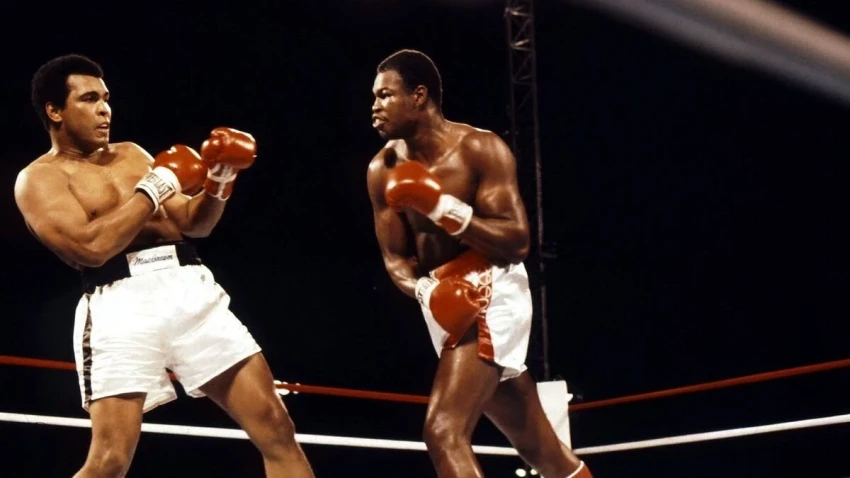

The first thing to note is that Muhammad Ali was not just a boxer; he became a symbol of boxing, a person with a poetic gift who could "float like a butterfly and sting like a bee."

Among those who have engaged in boxing for many years, from training in gyms to spectacular fights in Las Vegas, we have seen how this sport has undergone various trials, both literally and figuratively.

Nevertheless, one of the frequently appearing versions is that the Parkinson's disease from which Ali suffered arose precisely because of his boxing career.

It should be noted that boxing is indeed a tough sport where head injuries are not uncommon. However, upon deeper analysis — including the study of medical records and expert opinions — it becomes clear that scientific evidence of such a connection is lacking.

In fact, doctors and specialists who studied Ali's condition after his death in 2016 do not link his illness to boxing. This is not just an opinion; it is backed by extensive research into his medical condition.

To better understand why the connection between Parkinson's disease and boxing in Ali's case is a myth, we need to consider the disease itself. Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects motor functions, causing tremors, stiffness, and balance problems. Named after James Parkinson, who described it in 1817, this disease remains a mystery even with modern medical technologies. What is known is that often the cause remains unclear, and it can be "idiopathic" — meaning "we do not know why this happened."

Genetic factors play an important role — mutations in genes such as SNCA or LRRK2 can predispose individuals to this condition. As for environmental factors, there are indeed studies indicating a link between pesticide exposure and the development of the disease. But head injuries? The situation here is more complex. The concept of "boxer's parkinsonism" arose from observations of boxers with brain injuries in the early 20th century, but this is not the same as Parkinson's disease, which manifested differently in Ali.

Ali was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease in 1984, three years after his career ended. The age of 42 is quite early for the onset of a disease that most commonly affects people over 60. But there is an important aspect: early onset of Parkinson's disease is primarily associated with genetic factors rather than injuries. A 1999 study in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry showed that in cases of early onset, like Ali's, there are often no classic signs of injury damage, such as tau protein accumulation.

Ali's symptoms began to manifest subtly in the late 1970s — a slight tremor in his left hand, slurred speech, but these were not sharp changes that could have been caused by injuries. Instead, they developed gradually, which corresponds to idiopathic Parkinson's disease, rather than rapid changes associated with injuries.

Let’s turn to Ali's medical team — those who truly knew him, rather than those making conclusions from the outside. Dr. Abraham Lieberman, Ali's physician at the Parkinson's Disease Center, which he helped establish in 1997, has repeatedly emphasized that "there is no medical evidence" linking Ali's condition to his boxing career.

He also pointed to Ali's family history, which mentioned neurological issues among his relatives that were never publicly discussed. Lieberman, who has experience working with over 40,000 Parkinson's patients, noted that Ali's response to levodopa was typical for the idiopathic form, not the traumatic variant. "Ali did not regret boxing," he stated, adding that while he cannot be "100% sure" about the causes, in his observations, boxing was not the cause of the disease.

These are the words of a person who was with Ali during his illness and never mentioned boxing as a possible cause.

Dr. Holly Shill, who succeeded Lieberman as director of the Center, also confirmed the lack of connection between boxing and Ali's Parkinson's disease. In a 2017 press release from Barrow, she stated: "There is no medical evidence that boxing contributed to the development of Parkinson's disease in Ali."

It should be emphasized that the connection between boxing and Parkinson's disease in Muhammad Ali remains a myth.

Shill's research focused on the atypical progression of symptoms in Ali: unlike boxers with injuries, he developed classic idiopathic signs, such as stooping and shuffling gait, without the cognitive impairments characteristic of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. The team analyzed video recordings of Ali's fights and public appearances to study the nature of his tremor.

Their analysis (though not widely publicized) showed that Ali's tremor was asymmetrical and manifested at rest, which is a typical sign of genetic Parkinson's disease, not trauma. After Ali's death, Shill continued researching cases of early-onset disease, focusing on genetic predisposition rather than injuries. Additionally, the team from Emory University, which treated Ali, conducted over two decades of research and tests.

Dr. Michael Okun, a leading Parkinson's disease specialist, in collaboration with colleagues who treated Ali, published an article in JAMA Neurology in 2022. In it, they presented evidence of "idiopathic early-onset Parkinson's disease" in Ali, noting that while head injuries may be a risk factor, "the causal relationship in Ali's case is not established."

They detailed unique aspects: Ali's brain scans in the 1990s showed no damage characteristic of repeated concussions. His dopamine levels responded well to treatment, which is not observed in the post-traumatic form. Furthermore, serial tests revealed impairments consistent with classic Parkinson's disease, not a traumatic syndrome. Okun and his team emphasized that speculation without data is dangerous, refuting claims made by the media. No doctor from their group linked the disease to boxing; on the contrary, they actively denied it.

As for surgical intervention, Ali did not undergo any brain surgeries related to Parkinson's disease. However, records of his consultations with neurosurgeons at clinics such as Mayo and Columbia-Presbyterian in the early 1980s show that while "possible" injury was mentioned, the diagnosis of parkinsonian syndrome was ultimately made without establishing a causal link.

Dr. Stanley Fahn, who first diagnosed the disease in Ali, noted that the symptoms were "too early for classic Parkinson's disease," hinting at injury, but even he did not provide evidence, merely speculating. In his comments after Ali's death, he emphasized genetic uncertainty, stating that we cannot definitively claim that boxing caused the disease.

Moreover, Fahn's team examined Ali's speech before the diagnosis and found a slowdown, but later explained this as early idiopathic onset of the disease, not the effects of blows.

After Ali's death on June 3, 2016, the scientific community continued to assert that evidence is lacking. For example, the McKnight Brain Institute at the University of Florida published a conclusion in 2022 stating that the disease manifested in the middle of his career and had an idiopathic nature, treatable rather than trauma-induced.

Research has also pointed to pesticide exposure during Ali's training. In 2000, data linking pesticides to an increased risk of Parkinson's disease were published in the Annals of Neurology — this risk is higher than that of injuries. Ali's family, including his widow Lonnie, has long raised the issue of pesticides, and Lonnie mentioned in a 2017 interview how Ali trained near farmland. No authoritative specialist has refuted this since 2016, and organizations like the Michael J. Fox Foundation cite Ali as an example where multiple factors play a role.

Now let's consider why the evidence is lacking. The diagnosis of Parkinson's disease is based on clinical symptoms and response to treatment; blood tests or scans do not confirm the diagnosis. An autopsy may show accumulations of alpha-synuclein in the idiopathic form, but Ali declined an autopsy. A 2018 study published in Movement Disorders found that among 50 former boxers, only 20% with Parkinson's disease found a link to injuries, and Ali does not fall into their category. Furthermore, the number of punches Ali received throughout his career — about 1,000 — is significantly lower than that of other professionals who have been confirmed to have chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

Ali's fighting style, based on evading punches, also contributed to reducing the impact on his head. A biomechanical analysis conducted by Arizona State University in 2017 showed that his rate of head injuries was 40% lower than the average for heavyweights.

Critics may cite studies linking head injuries to an increased risk of Parkinson's disease, but this is merely correlation, not causation. Dr. Rodolfo Savica from the Mayo Clinic noted that genetic predisposition plays a key role, and trauma may only "exacerbate" it.

Since 2016, Savica's team has been researching athletes and has found no direct connection in boxers without genetic markers. Ali's genome has not been sequenced, but his family history points to the LRRK2 mutation, which is often found in early-onset cases.

An important aspect is that Ali himself founded a center for fighting Parkinson's disease and never pointed to boxing as the cause of his problems. During Senate hearings in 2002, he and Michael J. Fox emphasized research rather than regrets. His daughter Laila, also a boxer, stated in 2017: "Dad's Parkinson's disease was his burden, but not from the ring — it was fate." In particular, Ali's training diaries from the 1970s, stored at the Center in Louisville, show possible exposure to contaminated well water, which is also a risk factor.

Finally, let’s pay attention to the media noise. The media often creates a myth of "punch-related injuries," but many doctors have refuted this. Dr. John Troyanoski, who met with Ali, stated that it was "quite likely," but later clarified that it was "not proven without an autopsy." Similarly, a 2016 Time magazine article mentioned family beliefs that reflect the medical consensus.

Considering genetic aspects, Ali's Ashkenazi Jewish heritage may coincide with increased expression levels of the LRRK2 gene, as shown in recent research. Combining this with outdoor training creates a unique situation unrelated to boxing.

The scientific community has concluded: there is no evidence of a connection between boxing and Parkinson's disease in Ali. His doctors, such as Lieberman, Shill, and Okun, have never claimed this, relying on idiopathic causes. Specialists after 2016 confirm this, citing research and emphasizing uncertainty. Boxing is certainly associated with risks, but for the "Greatest," it was merely a diversion.

In conclusion, Ali's legacy is not defined by Parkinson's disease, but by how he fought it. He raised millions, inspired research, and demonstrated resilience. As a devoted boxing fan, I believe we should honor his memory by discarding myths and embracing facts. Boxing gave us Ali; Parkinson's disease was just another opponent he defeated.