Since the beginning of January, the main topic of discussion in Kazakhstan has been the work on a new Constitution. This topic has sparked active debates among the population, which is not surprising given that it concerns the fundamental document of the country. This was reported by Daniyar Moldabekov.

On one hand, the Center for Combating Disinformation under the SCC issued a rebuttal to a number of statements, although I do not claim that it is the only correct one — I merely note the fact. At the same time, there were no direct threats against citizens in its message, but there were accusations of clickbait attempts, which, in my opinion, is not always fair towards those who show interest in changes to the Constitution.

The authorities' reaction to the raised questions was relatively civilized: they decided to comment on the discussed statements. Why not?

Nevertheless, the Ministry of Internal Affairs got involved in the process. Although the law enforcement agencies acknowledged that "expressing opinions and positions does not violate the law," they still could not refrain from threats of criminal liability in case of spreading "knowingly false information."

It is worth reminding that "spreading knowingly false information" is a norm of the Criminal Code. Despite calls from experienced lawyers and human rights defenders for the liberalization of this article, the Union of Journalists of Kazakhstan (which I am not a member of and owe nothing to) stated at the end of last year about the need for its repeal.

As colleagues rightly noted, such issues should be resolved within the framework of civil law, not criminal law.

Nevertheless, the Ministry of Internal Affairs promises to "respond harshly to any attempts at destabilization." These threats seem exaggerated. One should not forget that it was the authorities who unexpectedly decided to rewrite the Constitution, not the citizens themselves.

Thus, the main responsibility for potential "destabilization" should lie with the Akorda and its subordinate structures, including the Ministry of Internal Affairs. If it were not for this sudden activity regarding the new Constitution, such a strong reaction would not have arisen.

These times are difficult; the population is burdened with loans and does not understand what will happen next, while the rest of the world is in chaos and tragedy. Threatening tired people for their words can also lead to destabilization, which no one wants. Everyone dreams of a calm, democratic, and free country, but for that, the authorities must also demonstrate democracy and civility.

And this is not just about the reaction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

The Akorda is trying to create an image of reform around the Constitution project, something absolutely new. However, the propaganda work in this direction looks clumsy and ineffective, as always. And the authors are the same.

Thus, the process of "reforms" is accompanied by old and familiar propaganda. Politicized Facebook is overflowing with posts from robot authors that could easily be replaced by artificial intelligence. Each thesis of the enthusiastic post is predictable even for a child.

"At the center of the new Constitution is the person, their freedoms, and the right to receive information that they are important for the new Constitution"… The same circle of authors with the same level of content on any topics: floods, taxes, weddings, and circumcisions — the new Constitution, and again in circles.

You can write anything in the Constitution. It is technically not difficult. However, it is much more important to live up to your own promises. Promising reforms and a new life, one cannot act according to old templates. Otherwise, reality may crack from such absurdity. Isn’t this potential "destabilization"?

Political scientist Dosym Satpaev notes:

The Pareto principle, according to which 80% of results are achieved through 20% of efforts, applies to the situation with the project of the new Constitution [of Kazakhstan].

This "updated" Constitution, rather than "new," as the emergence of new political institutions, such as a unicameral parliament and a people's council, essentially does not change the functions of the Basic Law in the current system, namely — the creation of explicit or hidden mechanisms to limit public participation in political life.

It is noteworthy that, while actively promoting the new constitutional reform, the authorities in the updated Constitution even expanded the tools for reducing citizens' electoral rights.

Firstly, the introduction of only a proportional model for forming a unicameral parliament from party lists automatically limits not only the right of citizens to be elected, as non-party candidates can no longer participate in elections, but also the right of voters to choose their representatives if they do not support any of the proposed parties.

Secondly, the "updated" Constitution retains a discriminatory clause, meaning that the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan can only be elected from among citizens with at least five years of experience in public service or elected positions, which excludes the majority of citizens from participating in presidential elections.

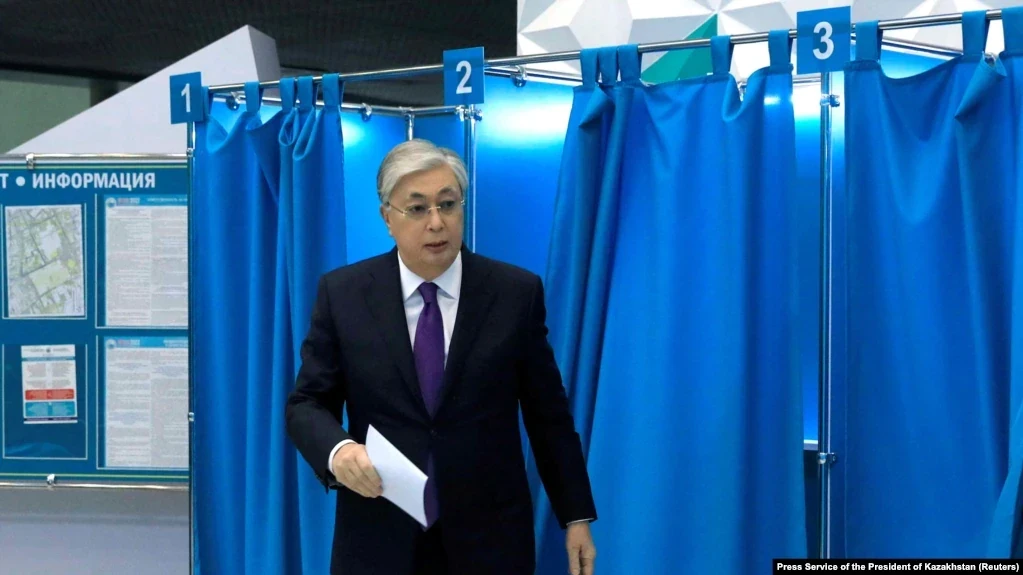

Interestingly, K. Tokayev now praises D. Trump and his initiatives, but within the framework of the "updated" Kazakh Constitution, Trump would have had no chance of becoming president.

Thus, returning to the Pareto principle, only about 20% of the articles in the Constitution (both old and updated) are of the greatest importance to the authorities. Most of them are aimed at preserving political monopoly both in political life and in matters of power succession.

By the way, these 20% also include new vague formulations that increase the possibilities for various interpretations, which, in turn, can lead to political abuses in the area of restricting freedom of speech and citizens' rights to assemble and protest.

When representatives of the authorities begin to talk about "morality," this should raise concerns. The authorities and their supporters are far from being examples of morality to determine what constitutes moral behavior and what does not.

In a political monopoly, any criticism of the authorities may in the future be deemed immoral. In the absence of a clear legal definition of what morality is, its interpretation becomes the prerogative of state bodies.

One of the chronic problems of authoritarian systems is the inconsistency of laws and regulations with the Constitution. Formally, the supremacy of the Basic Law is observed, but in practice, the will of the head of state or acts of executive power can violate the constitutional rights of citizens, hiding behind the interests of the state or national security.

At the same time, "national security" often means "the security of the ruling elite." This creates a desire among them to have more opportunities for "flexible interpretation" of the Constitution and laws, justifying the adoption of restrictive measures that contradict the declared rights and freedoms.

The reason for this is the weak control by state bodies that should monitor the compliance of laws with the Constitution. The absence of a system of checks and balances leads to the dependence of the judicial and legislative branches of power on the executive.

Creating a real system of checks and balances is a fundamental element of any serious constitutional reform. Without such a system, even the most advanced rights and freedoms enshrined in the Constitution will remain without adequate protection.