Abdygany Mamanov, who served in an aviation regiment, voluntarily went to Afghanistan and then continued his career in various countries, from Europe to Africa. However, he believes that the most important aspect of his service is the people he met through the war and the lessons he learned from it.

On the eve of the 37th anniversary of the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, he shared with 24.kg his experiences, including why he wrote a letter to the Minister of Defense of the USSR in his youth, how he managed to obtain scarce goods in Afghanistan, and why the depiction of war in films often differs from reality.

Reference 24.kg

The Afghan War of 1979–1989 was a conflict between the government of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, supported by Soviet troops, and Afghan mujahideen.

Although the Soviet Union quickly occupied most of the country, the insurgent movement, supported by the West and several Islamic states, proved to be strong.

Soviet troops entered Afghanistan on December 25, 1979, and the last soldier left the country on February 15, 1989. According to various estimates, the losses of the USSR amounted to 13,833 killed, 53,753 wounded, and 417 missing.

How a letter to the Minister of Defense led to service in Afghanistan

I entered the Kharkov Military Aviation Technical School, and being a native of Osh, it was not easy for me. My level of Russian was low, and I studied hard on weekends. The teachers noticed my efforts and inflated my grades on exams. By the second year, I started to study successfully.

When it came time for distribution, I asked the commander to send me to the Central Asian Military District, but he said they only sent slackers there. In the end, I was sent to the Prikarpatye Military District, which was considered one of the best.

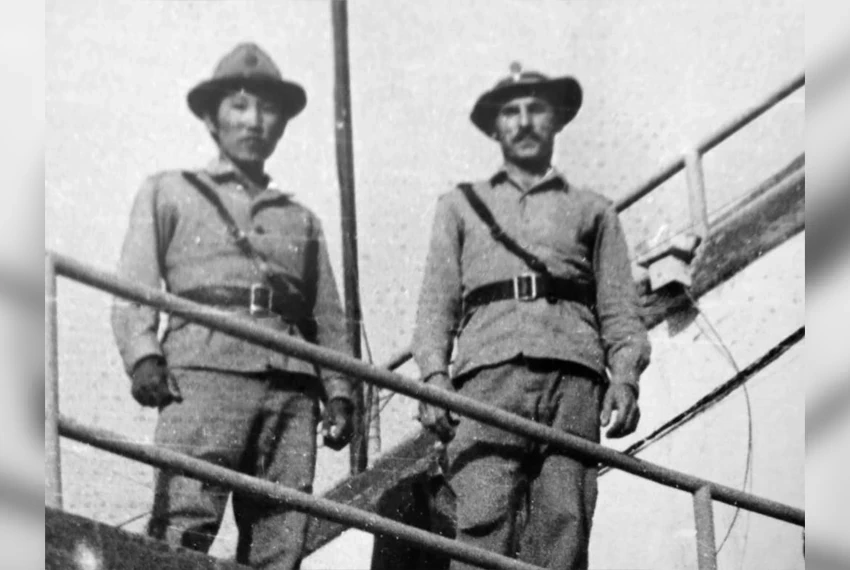

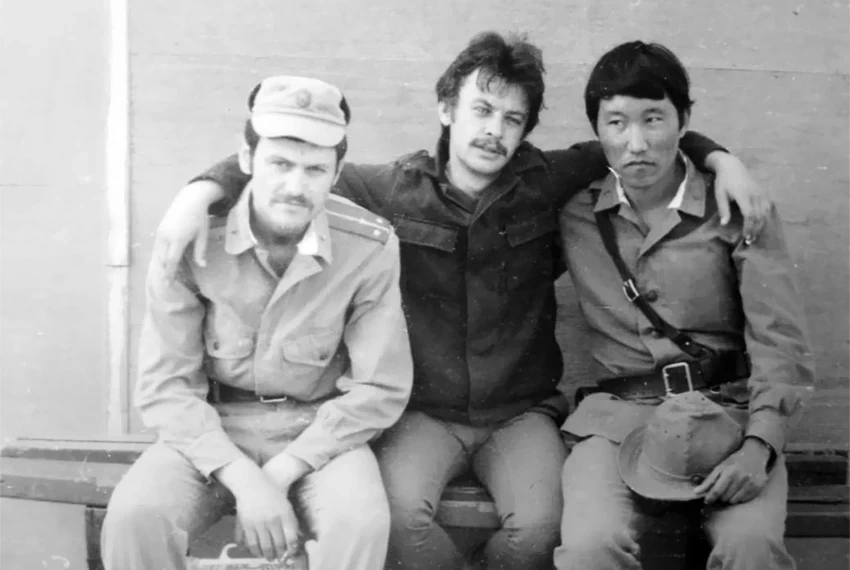

I lived for several years in western Ukraine, where I met wonderful people: Valery Moiseenko from Belarus, Igor Gnoevy from Russia, and Sasha Fedorenko from Ukraine. We became best friends.

In 1982, during the May holidays, we, inspired, wrote a letter to the Minister of Defense of the USSR. Such high-ranking officials were not addressed directly at that time, but we didn’t think about it.

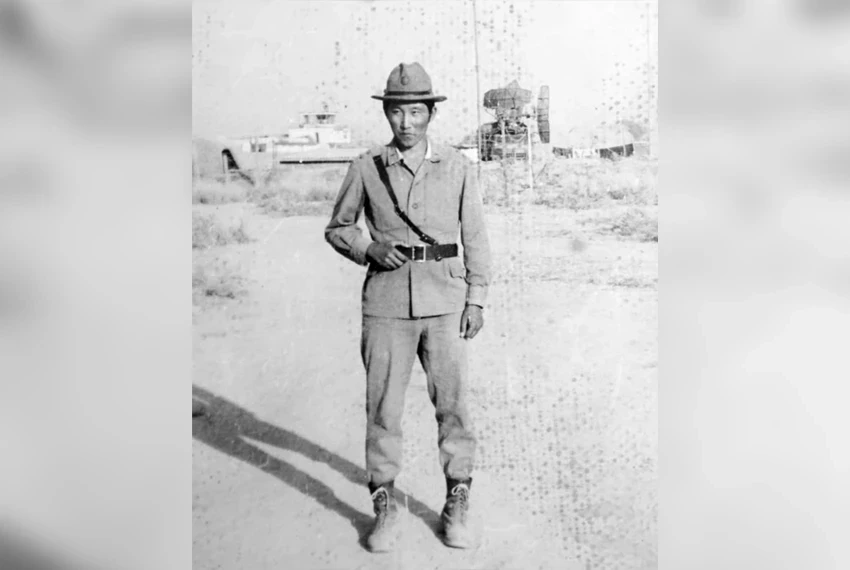

Abdygany Mamanov

We asked to send us to Afghanistan for international assistance. In the morning, when we decided to cancel the letter, it turned out to be too late — it had already been approved. Thus, on September 12, 1982, I found myself in Afghanistan.

Operations in Kunduz: hunting for mujahideen and aviation work

I served in an aviation regiment in Kunduz province, where we established communication for aviation, used tropospheric radio communication, and encrypted messages. We also corrected the strikes of Soviet troops.

Once we received information about a meeting of enemy commanders. We sent a Mi-8 helicopter with a flare bomb to their hideout. When it exploded, the assault aircraft and infantry moved in. The actions were coordinated: some mujahideen were eliminated, and the rest were captured.

Mujahideen often used simple clothing for camouflage, and there were no random people among them. We found detailed diagrams of Soviet helicopters with indications of vulnerable spots among the enemies, prepared by high-class foreign instructors.

Each mujahid had a document with information about their skills and experience, and they received bonuses for killed soldiers and destroyed equipment.

Scarcity, moonshine, and tears of a compatriot: daily life in Afghanistan

There were only two Kyrgyz officers in our unit. One of them was Senior Lieutenant Saifutdin Azizov — a true hero and the only sniper pilot in Kyrgyzstan.

One day, a man approached the fence of our airfield and, asking for water in Kyrgyz, told me that his grandfather had once moved to Afghanistan. I gave him two boxes of food that we had left, and he burst into tears, dreaming of one day visiting Kyrgyzstan.

I spent just under a year and a half in Afghanistan, of which seven months were in missions. I bought jeans and other scarce goods that were brought into the country from Japan and Hong Kong. However, the leadership did not approve of such purchases.

Some goods were also sold at our airfield, but at very high prices. I would change into civilian clothes and hide my weapon to go to the market. Sometimes, to relieve stress, I would buy moonshine — even though it smelled bad, it didn’t cause a hangover. I also visited friends from the academy — Sasha Fedorenko in Bagram and Valery Moiseenko in Kabul.

I observed how our pilots, representing different nationalities, worked as a team, and I realized that international crews are the most effective. Those who divide themselves by any criteria will not be able to win.

War: a tragedy, not romance

There are many films about military life that create the impression that war is romantic. In reality, it is a terrible tragedy. I saw young guys who lost their legs.

In the army, there are no holidays or personal life. You must be ready to carry out combat missions at any time, without sparing yourself. You are constantly learning and responsible for complex equipment. This requires nerves of steel, discipline, and complete dedication.

Nevertheless, I am grateful to Afghanistan for the friends we parted ways with more than 40 years ago, but true friendship knows no distance. We keep in touch through the internet, and some of the emigrants want to return.

One of my friends, a medical service major, married a German woman and moved to Germany. After his wife's death, he returned to Kyrgyzstan and spent 10 months performing complex operations, including heart surgeries. He wanted to stay but couldn’t find suitable work, so he moved back to Germany, where he quickly found a new position.

The life of a colonel after Afghanistan: from Germany to India

After returning from Afghanistan, I got married and served in Germany from 1984 to 1989, where my eldest son was born. Then I was in Orenburg, and in 1992, at the invitation of the Kyrgyz government, I returned to my homeland and joined the National Guard.

I went on missions to Russia and other countries. In 2002, I was sent to India to study English, and later I entered the military staff academy of the armed forces.

At that time, I was already a colonel, and I was settled in a separate cottage — like a king. In India, military personnel are respected, and after retirement, they do not need to look for work as security guards — they are offered decent vacancies.

In 2006, I went to Sudan as a peacekeeper under the UN, where I helped stop the civil war.

I served in the National Guard until 2007, and I was fortunate that General Abdygul Chotbaev was the commander, who did everything to make the National Guard a full-fledged military formation capable of performing any tasks. He still remains active and keeps us veterans in shape.

The last lesson in life

After retiring, I worked at the U.S. Air Force Transit Center at Manas Airport, where I held the position of senior representative from Kyrgyzstan in the engineering department, thanks to my knowledge of English.

The center provided cargo delivery to Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. I remember once the commander invited us for coffee and confessed that "Afghans do not like America, but they speak well of the USSR." The Soviet Union built a lot of infrastructure in Afghanistan, including houses, hospitals, and roads, and although the Afghans only realized this later, the assistance was significant.

Currently, I hold the position of chairman of the commission for patriotic and moral education of youth in the Oktyabrsky district of Bishkek. We conduct lessons in schools, universities, and military units to help young people realize the importance of their homeland. I notice that many are concerned about how to earn more without putting in effort, and they hardly think about their homeland. This is related to shortcomings in upbringing, and we are trying to correct this.

I do not approve of wars and do not like to discuss this topic. What is the point of fighting and losing lives if in the end there will still be a peace treaty? It is better to find common ground from the very beginning.